10 Facts About Education in Japan

- High school dropout rate: Japan’s high school dropout rate is at a low 1.27%. In contrast, the average high school dropout rate in the U.S. is at 4.7%.

- Equality in education: Japan ranks highly in providing equal educational opportunities for students, regardless of socioeconomic status. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Japan ranks as one of the highest in education equity. In Japan, only nine percent of the variation in student performance results from students’ socioeconomic background. In comparison, the average variation in the OECD is 14%, while the average variation in the U.S. is 17%.

- Teacher mobility: Japan assigns teachers to schools in a different way than most education systems. Unlike most countries, individual schools do not have the power to hire teachers. Instead, prefectures assign teachers to the schools and students who need them most. At the beginning of teachers’ careers, they move schools every three years. This helps teachers work in various environments instead of staying in one socioeconomic group of schools. As teachers advance in their careers, they move around less.

- Frugal spending: Japan does not spend a lot of money on its education system, with the Japanese government investing 3.3% of its GDP on education. This is over one percentage point less than other developed countries and is a result of Japan’s frugal spending. For example, the Japanese government invests in simple school buildings, rather than decorative ones. The country also requires paperback textbooks and fewer on-campus administrators. Finally, students and faculty take care of cleaning the school, resulting in no need for janitors.

- Teaching entrance exams: The teaching entrance exam in Japan is extremely difficult. It is of similar difficulty to the U.S. bar exam. Passing the exam results in job security until the age of 60, a stable salary and a guaranteed pension.

- Personal energy: Japanese education requires that teachers put in a great amount of personal energy. More common than not, many teachers work 12 or 13 hours a day. Sometimes teachers even work until nine at night.

- Emphasis on problem-solving: Teachers focus on teaching students how to think. Unlike some other countries that lean towards teaching students exactly what will be on standardized tests, Japan focuses on teaching students how to problem-solve. By emphasizing critical thinking, Japanese students are better able to solve problems they have never seen before on tests.

- Teacher collaboration: Japanese education highlights pedagogy development. Teachers design new lessons, and then present those to fellow educators in order to receive feedback. Teachers also work to identify school-wide problems and band together to find solutions. The education system constantly encourages teachers to think of new ways to better education in Japan and engage students.

- Grade progression:

Japanese students cannot be held back. Every student can progress to the next grade regardless of their attendance or grades. The only test scores that truly matter are the high school and university entrance exams. Despite this seemingly unregulated structure, Japan’s high school graduation rate is 96.7%, while the U.S. (where attendance and good grades are necessary to proceed to the next grade) has a graduation rate of 83%.

- Traditional teaching methods: Despite being one of the most progressive countries in science and technology, Japan does not use much technology in schools. Many schools prefer pen and paper. To save money, schools use electric fans instead of air conditioning and kerosene heaters instead of central heating. However, technology is now slowly being introduced into classrooms with more use of the internet and computers for assignments.

Through these methods, Japan has established that teaching and schooling are highly regarded aspects of society. By looking at what Japan has done, other countries might be able to learn and adapt to this minimalistic, equitable education model. – Emily Joy Oomen

ADMINISTRATION OF THE EDUCATION SYSTEM

Responsibility for educational administration and policy development is divided between government authorities at three levels: national, prefectural, and municipal. At the national level, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), or Monbu-kagaku-shō, is responsible for all stages of the education system, from early childhood education to graduate studies and continuing, or lifelong, learning. MEXT ensures that education in Japan meets the standards set by the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education which stipulates that the country provide an education to all its citizens “that values the dignity of the individual, that endeavors to cultivate a people rich in humanity and creativity who long for truth and justice and who honor the public spirit, that passes on traditions, and that aims to create a new culture.”

To fulfill that mandate, MEXT sets and enforces national standards for teacher certification qualifications, school organization, and education facilities, among others. It provides a significant portion of the funds for public schools, universities, research institutions, and, under certain circumstances, issues grants to private academic institutions. MEXT is also typically responsible for the development of national education policies, although in recent decades prime ministers have often convened ad hoc councils to determine education policy.

At the elementary and secondary levels, MEXT develops national curriculum standards or guidelines (gakushū shidō yōryō) which contain the “basic outlines of each subject taught in Japanese schools and the objectives and content of teaching in each grade.” Typically, private educational publishers develop and print textbooks following these guidelines. Elementary and secondary schools can only use textbooks reviewed and approved by MEXT, which provides textbooks to students free of charge.

Although MEXT revises the curriculum guidelines roughly once every 10 years, their overall structure and objectives have remained more or less the same since 1886. Since then, curriculum guidelines have emphasized standardization, objectivity, and neutrality to avoid divisive political, factional, and religious issues.

While this emphasis may lead one to assume that the national government strictly limits and controls educational content and teaching methods, in theory, these guidelines are only intended to establish nationally uniform standards of education, allowing students throughout the country access to an equal education.

The system is designed to give teachers the freedom to develop individualized lesson plans and tests. Still, comparisons with other OECD countries suggest that Japanese teachers have limited control over classroom instruction and curriculum. Among the recent concerns cited as limiting the freedom of Japanese teachers is the 2007 introduction of a national academic achievement test. Observers note that in order to reach achievement test targets, local schools and educational authorities have tightened control over teaching methods and educational content.

At the prefectural and municipal levels, the external influences mentioned in the introduction are readily apparent. In the post-World War II era, democratization and the decentralization of education were core issues of educational reform, spurring the Japanese government to adopt the system of boards of education common in the U.S.

Japan is divided into 47 prefectures, each of which is composed of smaller municipalities, such as cities, towns, and villages. Boards of education, representative councils responsible for the supervision of education at the elementary and secondary levels, exist at both the prefectural and municipal levels. At the prefectural level, governors appoint members to five-member boards of education for terms of four years.

Prefectural boards are responsible for appointing teachers and partially funding municipal operations and payrolls, including funding for two-thirds of teachers’ salaries, with the remaining third financed by the national government. At the municipal level, members are appointed by local mayors. Municipal boards are responsible for the supervision of day-to-day operational tasks at elementary and junior high schools, the management and professional development of teachers, and the selection of MEXT-approved school materials.

A 2015 reform of the board of education system—the first such reform in nearly 60 years—expanded the control of local chief executives, such as governors or mayors, over educational administration and planning, and reduced the role of boards of education. Authority to appoint the superintendent, the most powerful local educational authority, was transferred from the board of education to the local chief executives. The reform also increased their authority to determine local policy goals—it transferred authority to establish the local education policy charter to chief executives, reducing boards of education to an advisory role. Reformers hope the changes will lead to improvements in a system long criticized for its lack of transparency, accountability, and clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

Traditionally, two principal forms of early childhood education (ECE) have existed in Japan: kindergarten (yōchien) and day care (hoikuen). Under the jurisdiction of MEXT, yōchien is a non-compulsory stage of the country’s educational system, coming immediately before elementary school, providing preschool education to children from the ages of three to six.

Children typically attend yōchien for around four hours each day. As at other levels of Japan’s basic education system, MEXT develops and publishes curriculum standards for kindergartens, which must meet criteria necessary for the curriculum to realize the nation’s educational goals. The latest, issued in 2017, seeks to foster a “zest for living,” a goal pursued at all levels of the educational system, and lay the groundwork for learning at the elementary level and beyond.

Administered by a different ministry, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, hoikuen exists outside the Japanese educational system. Its principal function is to provide basic childcare services for children age one to six while their parents are at work. Typically lasting for eight hours, or the length of a typical working day, hoikuen often include some educational elements like reading and math.

Both yōchien and hoikuen centers can be owned and operated by public or private bodies, such as local municipalities, educational corporations, or non-profit organizations. However, the majority of students enroll at private institutions, some of which are highly selective and expensive. Many parents believe that enrolling their children in these highly selective institutions increases their children’s chances of being admitted to more selective institutions later in their educational career. In fact, some yōchien and hoikuen centers even prepare students for admissions tests at private elementary schools.

With more and more Japanese mothers entering the workforce, yōchien kindergarten programs, which have traditionally provided educational supervision for only part of the day, have in recent years faced

difficulty maintaining enrollment numbers. For the same reason, the demand for full-day hoikuen services has been on the rise. Historically, there have been long, persistent waitlists for parents hoping to enroll their children in hoikuen centers.

Given the clear demand for full-day childcare services, more and more yōchien have begun to adopt the day care elements more typical of hoikuen centers. For example, some yōchien have begun to offer extended hours to meet the demands of working parents, not ending their classes until the end of the workday. Some local governments have also started combining yōchien and hoikuen centers and mandating enrollment for all children prior to elementary school. The national government has even introduced measures merging childcare and early childhood education services into a single facility known as nintei-kodomoen. However, because of conflicting ministerial jurisdictions, reform efforts have often been stymied by administrative complications and are yet to achieve widespread success.

Still, early efforts at reform, combined with declining birthrates, have proved effective in reducing hoikuen waitlists. In 2019, waitlists for day care facilities reached an all-time low, with just under 17,000 children waiting to enter day care, a decrease of more than 3,000 children from the previous year.

ELEMENTARY AND LOWER SECONDARY EDUCATION

Elementary education marks the beginning of compulsory education for all Japanese children, lasting six years and spanning grades one to six. Children enter elementary education provided they reach age six as of April 1.

The elementary curriculum emphasizes both intellectual and moral development. All students must take certain compulsory subjects, like Japanese language, mathematics, science, social studies, music, crafts, home economics, living environment studies, and physical education. For public school students in grades five and six, English has been a compulsory subject since 2011. Since 2020, English has been mandatory starting in third grade. Moral development is promoted through a moral education course and informal learning experiences designed to inculcate respect for society and the environment. The importance of moral education—long a taboo subject given its association with the nationalistic excesses of Imperial Japan—to Japan’s educational policies has increased over the past few decades. In recent years, the reintroduction of moral education as a formal course was spurred by reports of rampant student truancy, bullying, and school violence.

Classes remain large by international and OECD standards, despite efforts by MEXT to improve student-teacher ratios and recruit additional instructors. In 2011, MEXT limited first grade classes to 35, down from 40, although intentions to extend similar limitations to other grades subsequently failed. Nearly all the country’s elementary schools, known as shōgakkō, are public. Enrollment at public elementary schools is free.

Students completing the elementary education cycle are awarded the Elementary School Certificate of Graduation (shogakko sotsugyo shosho) and automatically accepted into public junior high school.

Lower secondary education, the final stage of compulsory education, lasts three years, comprising grades six to nine. Instruction is conducted at junior high schools, or chūgakkō, 90 percent of which are public and tuition-free. Some municipalities have established nine-year unified compulsory education schools which combine primary and lower secondary education. Students hoping to enroll in private junior high schools or national junior high schools affiliated with national universities are required to sit for admissions examinations administered by the institution.

All public junior high schools follow a standard national curriculum which comprises the compulsory subjects previously taught at the elementary level. In addition to compulsory subjects, students can also choose from a wide range of electives and extracurricular activities in fields such as fine arts, foreign languages, physical health and education, and music.

Lower secondary education is a critical stage in a typical student’s educational journey, as grades partially determine whether a student will be accepted into a good senior high school, and consequently, into a top university. It also culminates in the first significant stage of what is colloquially referred to as “examination hell,” a series of rigorous and highly consequential entrance examinations that are required for admission to senior high schools and universities. Many students in the final two years of junior high school attend Juku, or cram schools, in preparation for the competitive senior high school admissions examinations.

Students completing junior high school are awarded the Lower Secondary School Leaving Certificate and are eligible to sit for senior high school admissions examinations.

Yutori Kyōiku: Compulsory Education Reform

Since the 1990s, the direction that education reform in Japan should take has been a hotly debated topic. Experts have long criticized Japanese education for its “strict management” which “places excessive emphasis on standardization and student behavioral control.” They have also voiced concerns about the “the widespread practices of rote memorization and ‘cramming’ of knowledge,” which have been accused of “depriving pupils of opportunities to develop their intellectual curiosity and creativity.” Finally, experts allege that the “intense competition among students vying for admission to prestigious senior high schools and universities has caused tremendous psychological pressure for these students and their parents.”

To address these concerns, the government issued national curriculum standards in 2002 that put in place a concept known as yutori kyōiku, which roughly translates as “relaxed education.” The updated guidelines brought about significant changes, reducing the length of the school week from six to five days and cutting curriculum content by 30 percent. The guidelines also mandated the creation of a new “Integrated Studies” course, which granted schools and municipalities discretion to create their own courses to provide students with a “learning space outside the traditional bounds of the curriculum that would not be closely associated with entrance tests or tightly defined learning outcomes.”

But a year after the new curriculum guidelines were introduced, yutori kyōiku policies faced intense criticism. The disappointing results of Japanese students in the OECD’s 2003 PISA study shocked the nation. In the study, the average performance of Japanese 15-year-olds dropped from first to sixth rank in mathematics and from eighth to 14th in reading. In just three years, mean performance had dropped from 557 to 543 in mathematics, from 522 to 498 in reading literacy, and from 550 to 548 in science.

Experts also highlighted the results of the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), an assessment that measures U.S. eighth grade student performance comparatively with that of other secondary students around the globe, as a sign of the country’s declining educational quality. While Japanese students again performed well overall, outperforming the global average in mathematics, when compared with other high-performing Asian countries, Japan’s performance was disappointing. Between 31 percent and 44 percent of students from Singapore, South Korea, and Hong Kong scored at the advanced benchmark for math, compared with just 24 percent of Japanese students. Many Japanese scholars attributed the Japanese students’ relatively poor performance in these international education assessments to the more relaxed nature of the yutori kyōiku reforms.

Public concern over declining performance prompted the Japanese government to review the yutori kyōiku reforms. What followed were a number of reforms aimed at maintaining some of the benefits of the educational reforms of the 1990s and early 2000s while increasing the academic rigor of Japanese compulsory education. MEXT issued new curriculum standards in 2008 and 2009 which increased academic lesson hours while reducing Integrated Study and elective hours, and a number of municipalities, supported by MEXT, reintroduced Saturday classes. MEXT also introduced mandatory foreign language courses to the elementary school curriculum, as mentioned above. More recently, reform in Japan has avoided the yutori kyōiku concept, instead promoting “Active Learning” with the aim of developing “students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes compatible with the new visions of learning for a knowledge-based society in the twenty-first century.”

UPPER SECONDARY EDUCATION

After nine years of compulsory education, students have the option of enrolling in senior high schools (kōtō-gakkō), widely regarded as the most strenuous stage of Japanese education. Despite being a non-compulsory level of education, the transition rate from junior to senior high school is extremely high, in part due to the integral role a student’s performance in senior high school plays in determining future access to higher education and employment. Per MEXT, as many as 98 percent of Japanese junior secondary students choose to move on to upper secondary schooling.

Admission to senior high school is typically determined by three criteria: an entrance examination, an interview, and junior high school grades. Of these criteria, the fate of a student’s placement in higher education—and even of their career in the years beyond—is determined most heavily by the entrance examination (kōkō juken). Students take these examinations, which are administered by their senior high school of choice, between January and March. Typically, entrance examinations test a student’s proficiency in the core subjects of Japanese, mathematics, science, social studies, and English.

Students hoping to enroll in public high schools take entrance examinations standardized by the prefectural board of education which has jurisdiction over the school. If students fail the entrance examination for a public school, they will often opt to apply to a private school. Unlike public schools, private senior high schools typically create their own examinations. Although nearly three-quarters of the country’s senior high schools are public, the proportion of private senior high schools has been growing in recent years. Students enrolling in the country’s limited number of unified junior high and senior high schools (chuto-kyoiku-gakko) are spared the entrance examination. Since reforms introduced in 2010, students have been able to attend public high schools free of charge, while students attending private high schools receive government subsidies.

The employment prospects of students who fail to gain admission to either a public or private senior high school are often grim, with many forced to find work as unskilled blue-collar laborers, an occupational category traditionally thought of as low status. Given the highly competitive nature of senior high school admissions and coursework, it is no surprise that senior high school is perceived as a vehicle toward higher social status. This exclusivity, however, has long raised concerns about equity and access. Since the 1980s, MEXT has attempted to rectify these concerns through a series of reforms, the most significant of which was the introduction of the credit system to senior high schools. In the late 1980s, MEXT implemented the credit system for part-time and distance education learners, allowing them to learn at their own pace and graduate when they completed the required number of credits. In the early 1990s, the credit system was expanded to full-time senior high school students as well.

Senior high school lasts for three years, comprising grades 10 to 12, with students receiving 240 days of instruction each year. Following recent yutori kyōiku-inspired educational reforms, the school week is officially five days long, from Monday to Friday. Still, as mentioned above, workarounds exist, with educational authorities issuing special approvals to public schools to hold Saturday classes, while many less regulated private schools have reintroduced Saturday classes at monthly or bimonthly intervals.

As at the lower secondary level, the senior high school curriculum comprises three years of mathematics, social studies, Japanese, science, and English, with all the students in one grade level studying the same subjects. Electives are also similar to those offered at earlier levels, including physical education, music, art, and moral studies courses. However, the high number of required courses often leaves students with little room to fit in electives or subjects matching their personal interests. Although MEXT has pushed to expand the types of courses taken in high school to promote individuality, purpose, and inspiration, implementation has proved difficult because of a lack of qualified teachers.

Students must obtain a minimum of 74 credits to graduate. Students who graduate are awarded the Senior High School Graduation Certificate (sotsugyo shomeisho) and are eligible to sit for university entrance examinations.

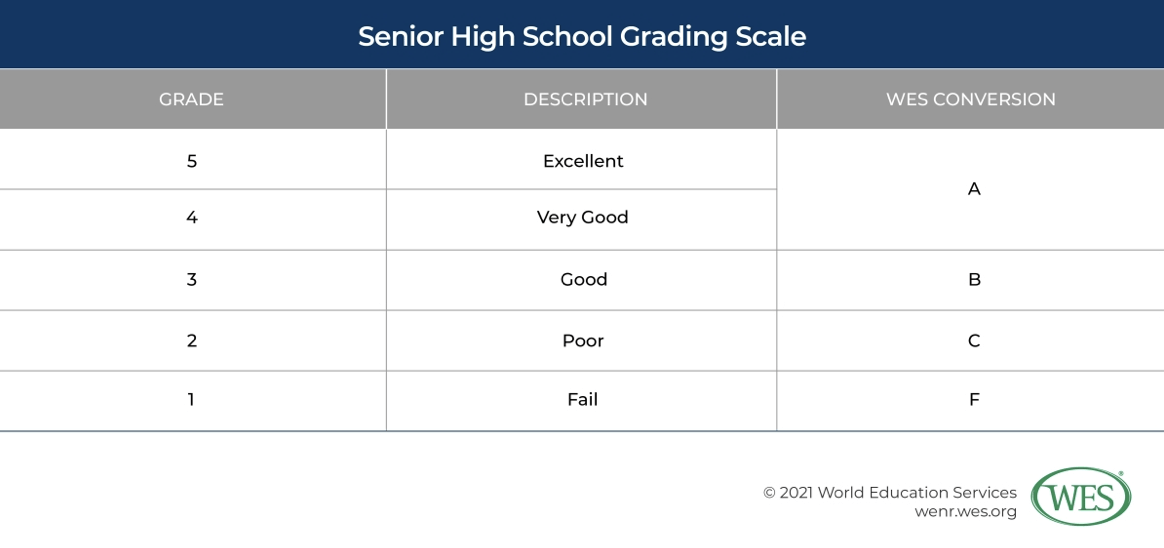

Senior high schools use a numeric grading scale ranging from 1 to 5.

TECHNICAL, PROFESSIONAL, AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

Amid Japan’s current economic challenges, technical and vocational institutions have attracted considerable attention from reformers and government planners. Concerns that the education system is “obsolete and dysfunctional, with the curricula lacking relevance to the realities of society and the economy,” has led to calls to expand and strengthen vocational and professional education. A 2017 MEXT white paper, which laid out key priorities in education reform, included a call to strengthen and reform the country’s technical and vocational education.

To meet the challenges of globalization, economic transformation, and declining birthrates, the paper highlighted the importance of diversifying the country’s education system by increasing the availability of vocational schools and junior colleges. That paper followed a 2016 revision to the 1947 School Education Act; the revision urged professional institutions to collaborate with industry leaders to develop curricula that better balance practical and theoretical components.

Government planners are hoping that these efforts will expand and strengthen what is an already diverse landscape of vocational and professional institutions. Japan possesses a wide variety of institutions offering specialized education and professional and technical training to Japanese students at the secondary, post-secondary, and continuing education levels. Given the unique recruitment practices of Japanese employers—discussed further below—these institutions are attracting a growing number of university students who choose to study in a vocational institution either simultaneously or after graduating from university, to increase their employability, a phenomenon known in Japan as “double schooling.”

Specialized Training Colleges (senshu gakku)

First introduced in 1976, specialized training colleges (senshu gakku) offer courses of study aimed at developing skills and competencies that are needed for specific occupations. Three categories of specialized training colleges exist: general, upper secondary, and post-secondary, each maintaining different requirements for admission and offering training programs that vary in content and intensity.

Most specialized training colleges are privately owned and operated. New specialized training colleges must meet minimum quality requirements set by MEXT, after which they can be granted approval to operate by the prefectural government in which they are located.

Specialized Training College, General Course (senshu gakko ippan katei)

The lowest level of specialized training college offers courses in general vocational subjects such as Japanese dressmaking, art, and cooking. MEXT does not set admission requirements for entry to general courses, instead allowing individual institutions to set their own. As of 2017, there were 157 colleges offering general courses to around 29,000 students.

Specialized Training College, Upper Secondary Course (koto-senshu-gakko)

More popular are the specialized training colleges offering courses at the upper secondary level. As of 2017, 424 institutions offered upper secondary courses to around 38,000 students. Admission to courses at this level requires possession of the Lower Secondary School Leaving Certificate. Courses typically last between one and three years. Those completing a course lasting three years or more that meets minimum academic requirements set by MEXT are eligible for enrollment in a university or a professional training college. Students graduating from these courses are awarded a Specialized Training College Upper Secondary Certificate of Graduation.

Professional Training College (senmon gakko)

The highest level of specialized training college is the professional training college, which offers courses at the post-secondary level. Admission is open to graduates of senior high schools, with courses lasting between one and four years. Students who graduate from specialized vocational schools are able to enroll in a traditional four-year university but can also use their degrees directly toward careers in their specialty. Options for specialization are vast but are typically classified into eight fields of study: industry, agriculture, medical care, health, education and social welfare, business practices, apparel and homemaking, and culture and the liberal arts.

Students completing a MEXT-approved course of at least two years and 62 credits (1,700 credit hours) are awarded a diploma (senmonshi). Those completing a MEXT-approved course of at least four years and 124 credits (3,400 credit hours) are awarded the advanced diploma (kodo senmonshi).

With birthrates falling and universities accepting a higher percentage of applicants, professional training colleges have struggled to maintain enrollment levels. Still, as of 2017, 2,817 professional training colleges existed, offering courses to around 660,000 students or around 15 percent to 20 percent of senior high school graduates. To encourage enrollment, some professional training colleges have adopted a dual education approach, organizing class schedules in a manner that allows students to study for a vocational diploma and a university degree simultaneously (the double schooling mentioned above).

Colleges of Technology (kōtō-senmon-gakkō or KOSEN)

Unlike other vocational institutions, colleges of technology, which were introduced in 1961, provide education and training that straddles the secondary and post-secondary levels. Students who are 15 years of age, or those completing junior high school, are able to study in these colleges, which primarily offer courses in engineering, technology, and marine studies. Programs typically last for five years, requiring 167 credits. Students who complete programs from colleges of technology are awarded a title of Associate (jun gakushi).

Colleges of technology are growing in popularity among university graduates who fail to secure employment immediately after graduation.

Professional and Vocational Junior Colleges (tanki daigaku)

A subset of junior colleges, discussed below, professional and vocational junior colleges (PVJC), pursue “teaching and research in highly-specialized fields with the aim to develop practical and applicable abilities needed to take on specialized work.” Programs at PVJCs are two or three years in length, requiring 62 to 93 credits, one-third of which must be earned in “practicum, skills training, or experiment,” including “on-site training conducted off-campus.” Students completing their studies are awarded the associate degree (professional) and are able to transfer to a general university or a professional and vocational university.

Professional and Vocational Universities (senmon shoku daigaku or PVU) and Professional Graduate Schools (senmon shoku daigakuin)

Other HEIs include professional and vocational universities (senmon shoku daigaku, or PVU), which offer courses similar to those offered at PVJCs and award four-year, 124 credit bachelor’s degrees (professional).

Professional Graduate Schools (senmon-shoku-daigakuin), which “specialize in fostering highly-specialized professionals who will be active internationally” and include law schools and schools for teacher education, award graduate professional degrees, such as the Juris Doctor and other professional master’s degrees. Programs range from one to three years in length with widely varying credit requirements. These professional degrees often meet eligibility prerequisites to sit for professional examinations; for example, a Juris Doctor is required to sit for the national bar examination.

Nursing Education

Before sitting for their national licensing examinations, nurses in Japan must complete at least three years of post-secondary education and training. Midwives and public health nurses must study for an additional year in a specialized program. Nursing programs are taught at a variety of institutions; universities, junior colleges, and nursing schools (kangoshi-senmon), which are overseen by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW), offer three-year programs in general nursing and one-year specialized programs in public health or midwifery. Universities are the only institutions authorized to offer four-year nursing programs, which often include a year of specialized training in midwifery or public health and lead to bachelor’s degrees in nursing.

Nursing programs typically follow a standard curriculum set by MEXT and MHLW. Students who successfully complete three years of general nursing education are eligible to sit for the National License Examination for Nursing; a high passing score allows them to begin practicing. After receiving their general nursing license and completing an additional year of specialized training, students can sit for National Public Health and National Midwifery Examinations.

HIGHER EDUCATION

Japan offers a wide and diverse landscape of HEIs that comprises junior colleges, universities, and graduate schools in addition to the post-secondary professional and vocational institutions touched on above. The country has one of the largest higher education sectors in the world, with around 3.9 million students enrolled in post-secondary education in 2018. That same year, a total of 2.9 million students were enrolled in universities, with 2.6 million enrolled in undergraduate programs and 254,000 in graduate programs. Enrollment rates are also high; according to MEXT, in 2017, the percentage of 18-year-olds studying at the post-secondary level was 81 percent, with 53 percent studying at a university, 22 percent at a specialized training college, 4 percent at a junior college, and 1 percent at a college of technology.

Three categories of Japanese universities exist: national universities, established by the national government; public universities, established by prefectures and municipalities; and private universities, established by educational corporations. One noteworthy characteristic concerning the composition of Japanese HEIs is the country’s high proportion of private institutions, which expanded rapidly in response to growing demand for higher education in the postwar economic boom years. In 2018, less than a quarter of Japan’s 782 universities were public or national—with just 86 national and 93 public universities, compared with 603 private universities. That same year, private institutions enrolled nearly four-fifths of all higher education students, giving Japan the seventh-largest private higher education student population in the OECD.

However, despite making up the majority of Japanese HEIs, private universities are often considered less prestigious than their national and public counterparts. Even today, national and public universities typically rank higher on domestic and international league tables and are responsible for the bulk of Japan’s academic research output. Of the 11 universities making up RU11, a consortium of Japan’s top research universities, only two are private, Keio University and Waseda University. Even more prestigious are the National Seven Universities, a group of national universities established and operated by the Empire of Japan until the end of World War II, the oldest and most prestigious of which is the University of Tokyo.

Recent reforms have helped modernize Japan’s highly respected national universities. The National University Corporation (NUC) Act , implemented in 2004, reorganized this HEI category, which had previously been managed directly by MEXT, transforming national universities into public corporations, a move that expanded their autonomy in academic, budgetary, and other matters. The NUC reforms also empowered national university presidents, allowing them to make important organizational, strategic, and academic decisions without statutory or MEXT approval.

Still, despite its size and diversity, higher education in Japan remains more challenged than any other stage of the country’s educational system. Problems include quality concerns, growing inequality, and shrinking enrollment. Japan’s population decline has meant that fewer and fewer students graduate from senior high school and that fewer are eligible to enroll in universities. Although the population of 18-year-olds has remained more or less steady for the past decade, MEXT projects that from 2021 onward, the decline, which was uninterrupted from 1991 to 2009, will begin again. The decline has had and will likely continue to have far-reaching ramifications in the higher education sector. As mentioned above, the decline has also prompted the Japanese government, universities, and higher education associations to look overseas for students to fill empty university seats. It has also driven some universities to ease admissions standards, replacing strenuous entrance examinations with interviews and student essays.

Educators have long been concerned with the quality, rigor, and purpose of education at Japanese universities. In contrast to the rigor of secondary education, university studies are typically considered easy, with students sailing through the first two and a half years before focusing on the job search in their final year and a half. The unique Japanese system of shūshoku katsudō (job hunting), long the country’s predominant recruitment practice, has meant that university education and the job market are more intimately connected in Japan than they are almost anywhere else in the world. Under the system, companies recruit exclusively from among new or soon-to-be university graduates, rarely hiring older job seekers. Once hired, these new university graduates often remain at the same company for life, with pay highly correlated with seniority, a system of employment known as shūshin koyō. As new graduates typically have little to no practical experience, recruiters place enormous emphasis on the prestige of a job seeker’s university and senior high school. Top employers, such as the Japanese government and the country’s largest companies, hire almost exclusively from Japan’s most prestigious universities. Job seekers who do not have a university education, and students attending an overseas university that follows a different academic calendar, face extreme difficulties obtaining employment.

The importance of a university education is reflected in employment rates. According to a 2012 OECD study, the employment rate for both men and women who hold a university education is significantly higher than for those with just an upper secondary education. The study also revealed a large gap in employment between men and women. Among men, 92 percent of those with a university education and 86 percent of those with an upper secondary education were employed, compared with just 68 and 61 percent of women with a university and an upper secondary education, respectively. Gender inequality is a widely recognized issue throughout Japan, not only in the workplace, but also in higher education. In a series of investigations, beginning at Tokyo Medical University in 2018, found that a handful of universities were systematically manipulating their entrance examination scores, lowering the test scores of women to ensure that they made up only a small minority of all admitted students. After the scandal forced Tokyo Medical University to make corrections, more women than men passed the entrance examination.

Japan’s singular reliance on private sources to fund higher education further exacerbates concerns about unequal access to a university education. As students at all universities, whether national, public, or private, pay tuition fees, private sources, such as students and their parents, fund a comparatively large share of Japanese higher education. The share of private expenditure on higher education, reaching nearly 69 percent in 2017, is among the highest in the OECD. Additionally, few scholarships or grants are available to students who need them, and a large proportion of Japanese students take out private or government-sponsored loans to fund their studies, raising concerns about the ability of less well-off individuals to obtain a university education and a comfortable post-graduation career.

Critics have also highlighted a mismatch between the education and skills imparted at the country’s universities and those needed to prosper in the modern world. In response, policymakers in Japan have called for the “internationalization” (kokusaika) of universities to better prepare students to navigate and succeed in an interdependent global economy. In many cases, these internationalization efforts have gone furthest in private universities, while national and public universities have struggled to adapt. In a 2008 survey conducted by MEXT, only 5 percent of faculty members in Japan’s most prestigious public institutions came from overseas.

University Admissions

“Thus there is a general belief that a student’s performance in one crucial examination at about the age of 18 is likely to determine the rest of his life. In other words: the university entrance examination is the primary sorting device for careers in Japanese society. The result is not an aristocracy of birth, but a sort of degree-ocracy.”

Despite the passage of half a century, those words, written in a review of Japan’s national education policies that was published by the OECD in 1971, still ring true today. Attending a prestigious university has a direct impact on one’s employment and life prospects, making the university admissions process one of the most significant stages of Japan’s educational system. While MEXT encourages universities to consider a range of factors when making admissions decisions, such as interviews, essays, and secondary school grades, entrance examinations are far and away the most important factor.

Students with a Senior High School Graduation Certificate who want to enroll at public universities or certain private universities typically take two entrance examinations: the National Center Test for University Admissions (daigaku nyūshi sentā shiken), more often referred to simply as the National Center Test or Center Test; and a university-specific entrance examination. National Center Tests, administered by the National Center for University Entrance Exams, are held annually over two days in January. There are 30 tests total, all multiple-choice, in six subjects: geography and history, civics, the Japanese language, foreign language, science, and mathematics. Students can sit for up to 10 examinations over the two days, typically choosing subjects required by their preferred universities for admission.

Institution-specific examinations at prestigious universities are often even more difficult than the National Center Tests. Students often elect to sit for multiple institution-specific examinations at several universities in case they do not get in to their preferred university. Prior to both examinations, universities distribute booklets to students to help them prepare for the subject examinations.

Criticism and Reform: The Common Test for University Admissions

Many Japanese policy experts have criticized the National Center Test, alleging that the test’s outdated emphasis on rote memorization contributes to a lack of independent and critical thinking in Japanese students. They also contend that the high-stakes nature of the test inflicts significant psychological distress on students and their parents, even going so far as to assert that the test reinforces a centuries-old cultural stigma that associates failure with being ostracized. For example, a large number of students who fail to achieve scores high enough for admission to their preferred university elect to retake the entrance examinations the following year. These students, who made up one-fifth of all students sitting for the National Test in 2011, are known as rōnin, a term that historically referred to wandering samurai stripped of their social status by the loss of their feudal master. Rōnin opting to study in a Juku, or cram school, which students can attend both before or after they sit for an entrance test, are typically relegated to a specific section of the school, segregated from other students. There, they subject themselves to long, grueling hours of study in hopes of raising their test scores high enough to gain admission to the college of their choice.

The test has also been decried for its lack of accessibility. Test prices are high and can cost students up to 18,800 Japanese yen, or around US$180, for just three subjects.[1] Cram schools can cost far more. Yobikō, which like Juku prepare students for entrance examinations, can cost as much as a year of university tuition. These high costs exacerbate economic inequality in an already-stratified Japanese society, stirring up tensions by furthering the impression that only the most socially and financially fit will be admitted to top-tier universities and, in turn, be guaranteed high-paying jobs in the future.

To address some of these issues, the Japanese government plans to replace the National Center Test with the Common Test for University Admissions, or Common Test, scheduled to be held for the first time in 2021. MEXT hopes that the new Common Test will select “entrants based on a multifaceted methodology that ‘fairly’ evaluates the skills that individuals have built up for themselves,” encouraging critical and independent thinking and deep analysis of problems instead of rote memorization. One means of achieving these goals is the introduction of written sections for mathematics and Japanese language tests. The significance of the new Common Test is enormous. It not only reveals a willingness to adapt to the demands of an ever-more globalized, knowledge-based world, but also signals a reevaluation of deep-seated cultural values, especially those of success, fairness, and individuality.

Sources:

https://borgenproject.org/education-in-japan/

https://wenr.wes.org/2021/02/education-in-japan

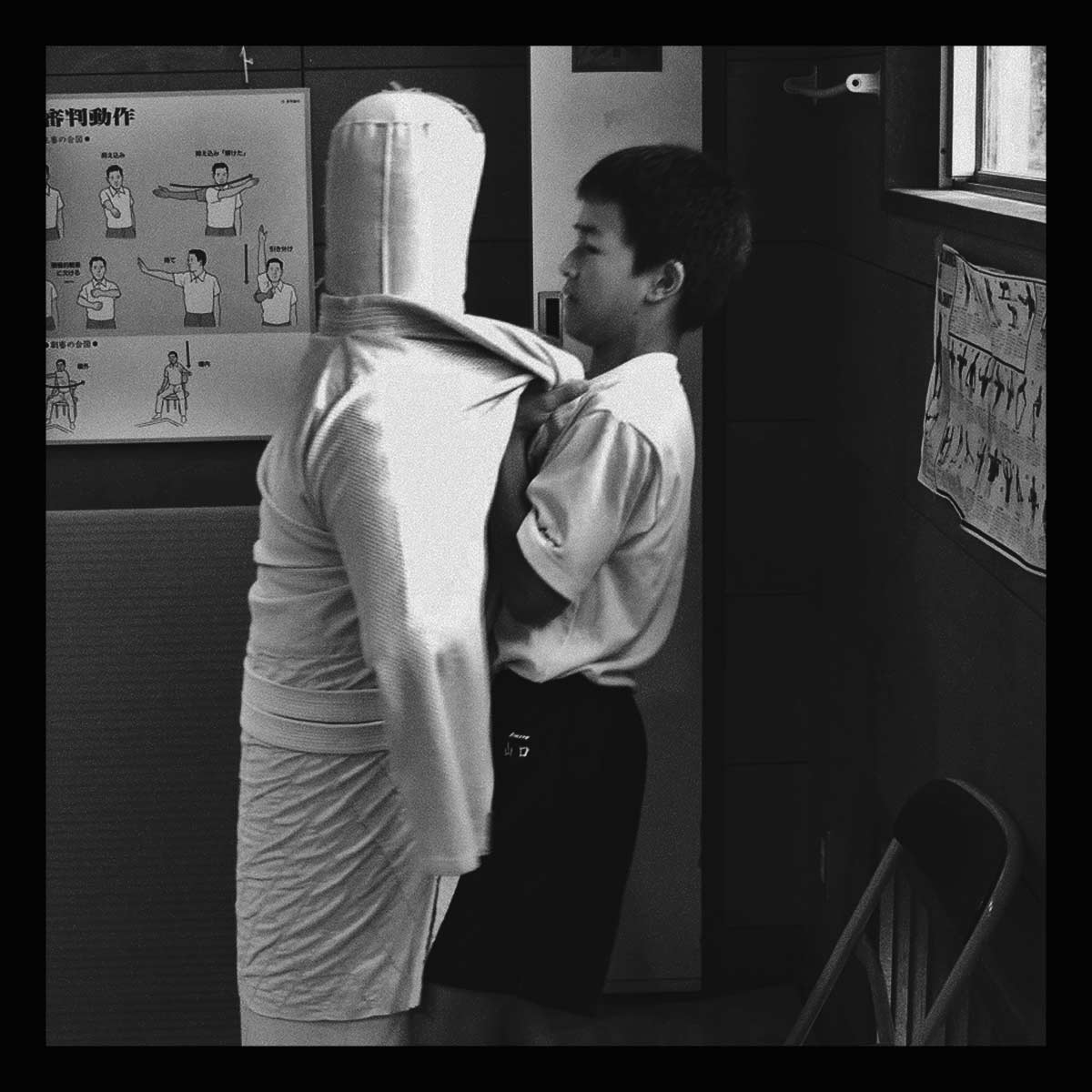

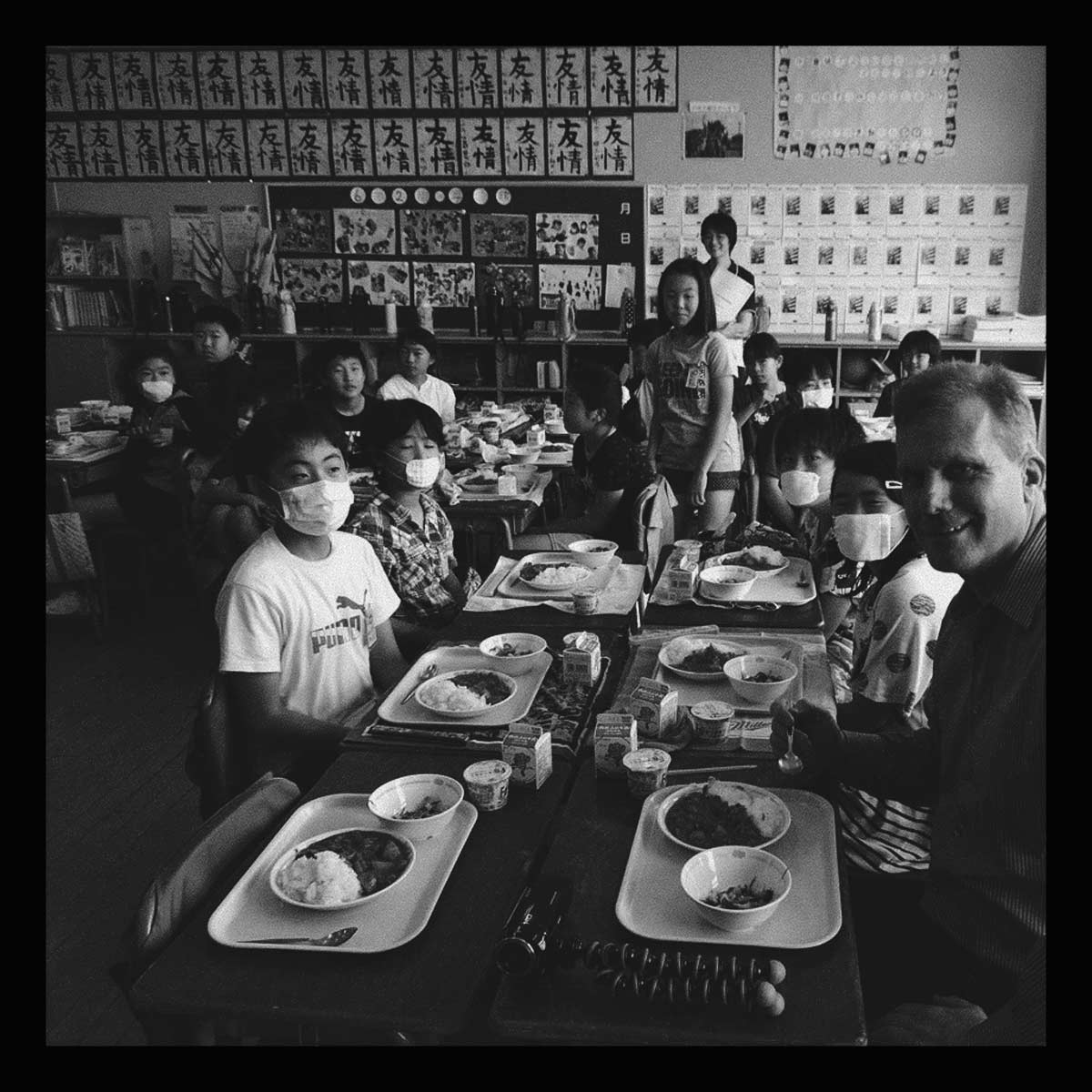

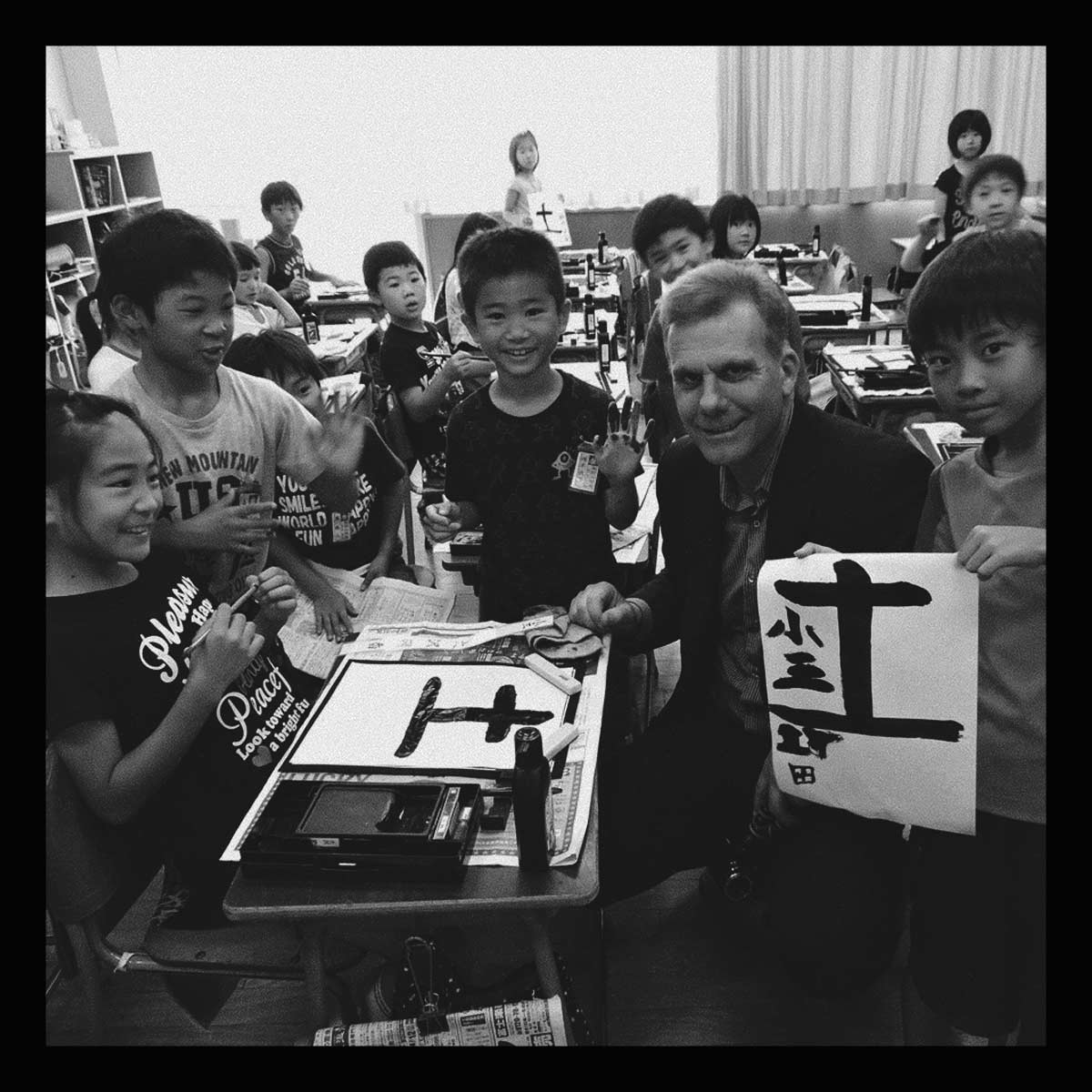

VIDEO GALLERY

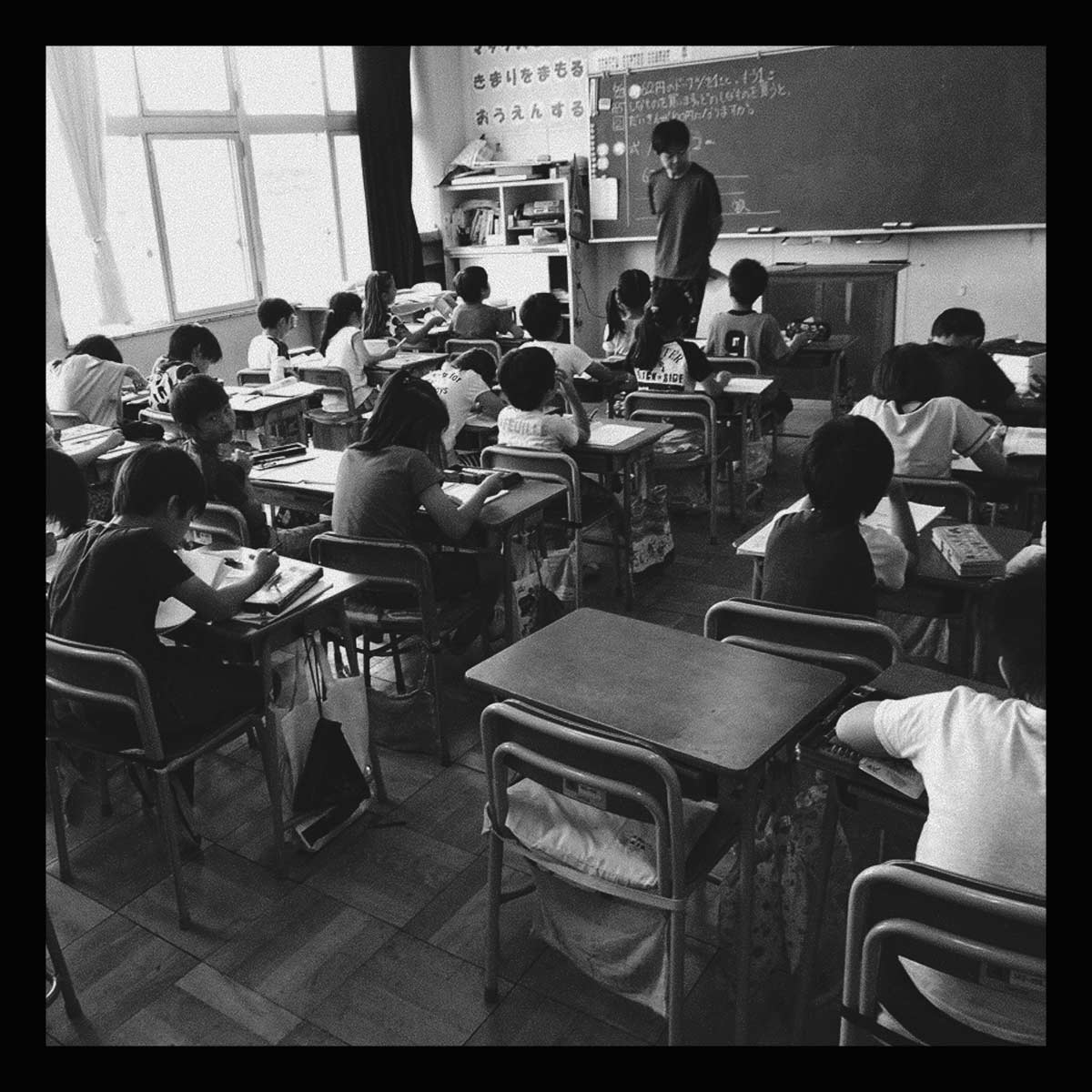

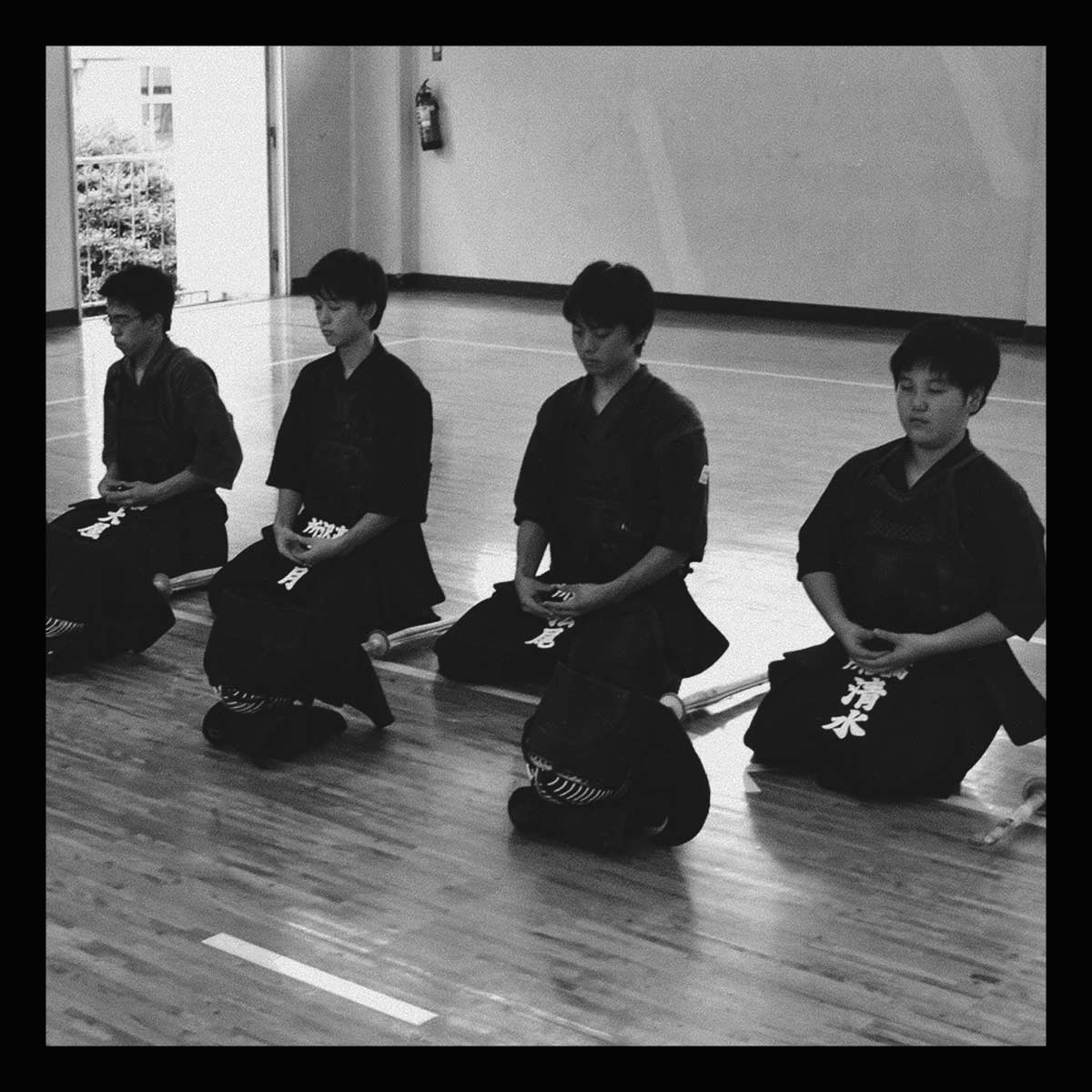

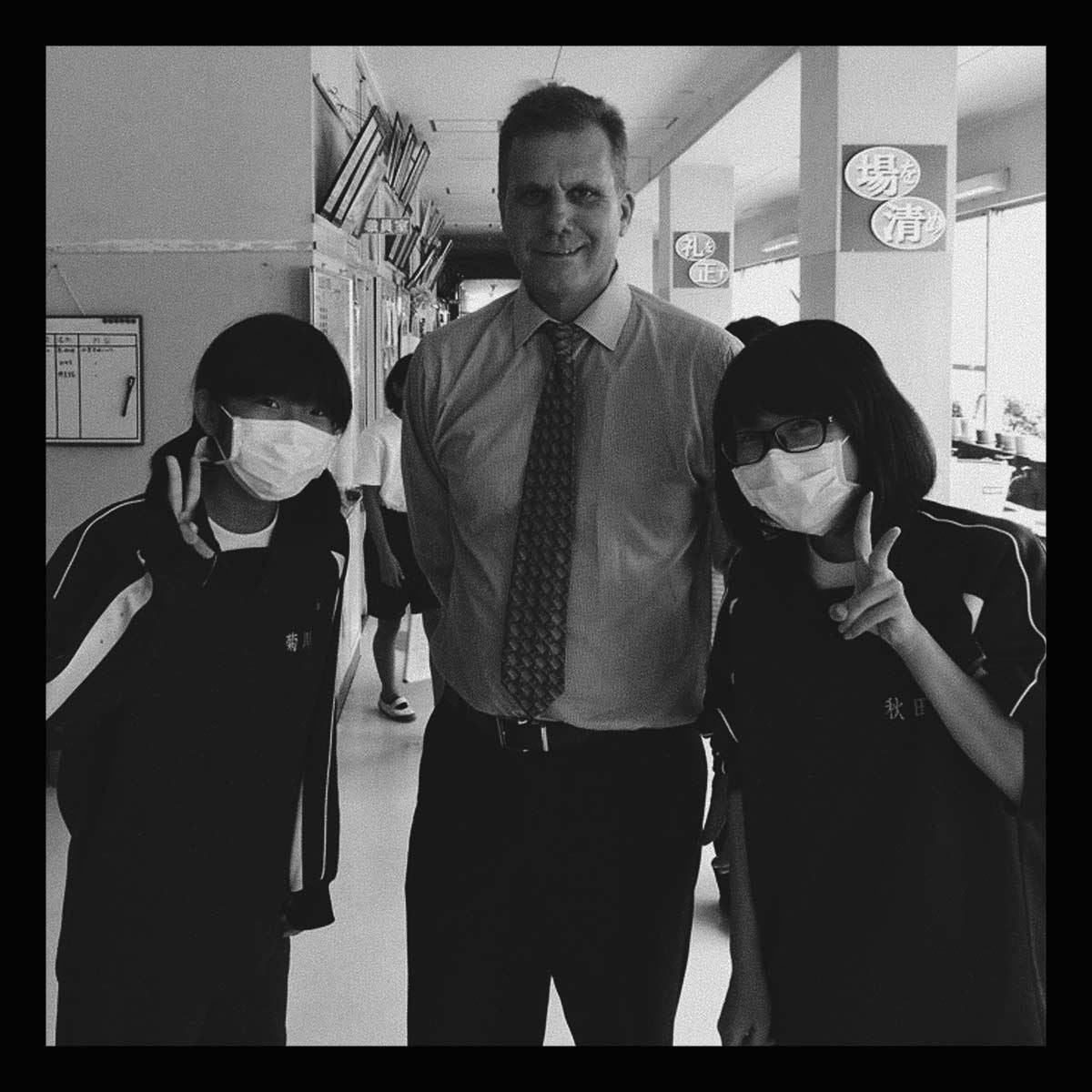

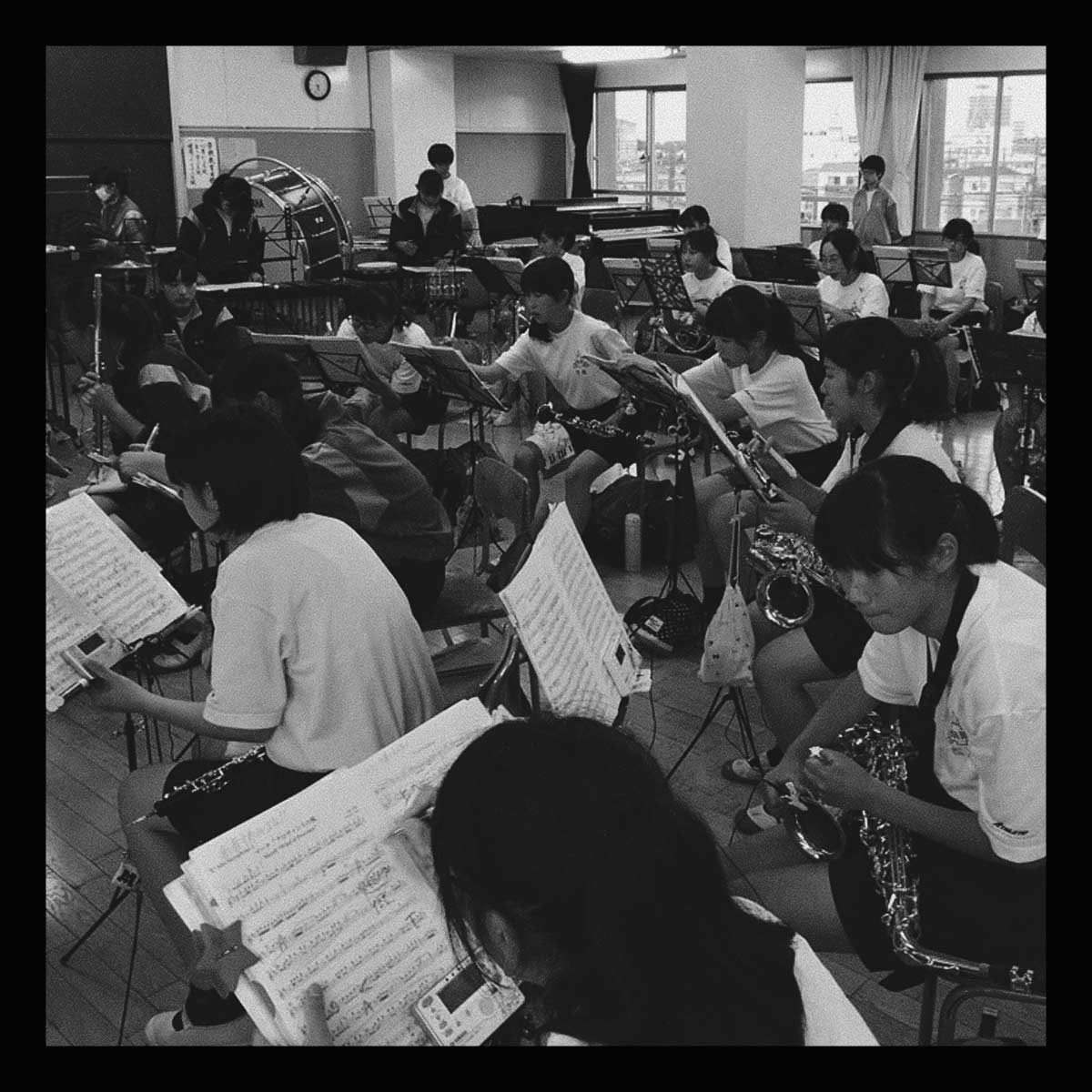

A few highlights from Keith's travels to Japan.

Share Page

STEALING FROM THE WORLD'S BEST SCHOOLS

What One U.S. Teacher Learned By Visiting Countries That Are Doing Education Right.