The speed of China’s emergence as one of the world’s most important countries in international education has been nothing short of phenomenal. Within two decades, from 1998 to 2017, the number of Chinese students enrolled in degree programs abroad jumped by 590 percent to more than 900,000, making China the largest sending country of international students worldwide by far, according to UNESCO statistics. This massive outflow of international students from the world’s largest country—a nation of 1.4 billion people—has had an unrivaled impact on global higher education.

The presence of large numbers of Chinese students on university campuses in Western countries is now a ubiquitous phenomenon. There are three times more Chinese students enrolled internationally than students from India, the second-largest sending country. The expenditures and tuition fees paid by these students have become an increasingly important economic factor for universities and local economies in countries like the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. In Australia, for instance, 30 percent of all international students were Chinese nationals in 2017. These students generated close to USD$7 billion in onshore revenues helping to make international education Australia’s largest services export.

China’s own education system has simultaneously undergone an unprecedented expansion and modernization. It’s now the world’s largest education system after the number of tertiary students surged sixfold from just 7.4 million in 2000 to nearly 45 million in 2018, while the country’s tertiary gross enrollment rate (GER) spiked from 7.6 percent to 50 percent (compared with a current average GER of 75 percent in high income countries, per UNESCO). By common definitions, China has now achieved universal participation in higher education.

Consider that China is now training more PhD students than the U.S., and that in 2018 the number of scientific, technical, and medical research papers published by Chinese researchers exceeded for the first time those produced by U.S. scholars. China now spends more on research and development than the countries that make up the entire European Union combined, and it is soon expected to overtake the U.S. in research expenditures as well.

Chinese higher education institutions (HEIs) currently pump out around 8 million graduates annually—more graduates than the U.S. and India produce combined. That number is expected to grow by another 300 percent until 2030. Needless to say, this massification of higher education has been accompanied by an exponential growth in the number of HEIs. The BBC reported in 2016 that one new university opened its doors in China each week. Altogether, China now has 514,000 educational institutions and 270 million students enrolled at all levels of education.

What’s more, China’s top universities now provide education of increasingly high quality. Long absent from international university rankings, top-tier universities are now increasingly represented among the top 200 in rankings like those of the Times Higher Education (THE). Fast-ascending flagship institutions like Tsinghua University and Peking University are now considered to be among Asia’s most reputable institutions and appear in the top 30 in both the THE and QS world university rankings. In fact, Chinese universities’ quality improvements and other factors have helped turn China itself into an important destination country of international students from Asia, Africa, and elsewhere.

RAPID ECONOMIC GROWTH

All these developments are part and parcel of China’s spectacular economic growth since the adoption of Deng Xiaoping’s economic liberalization reforms in 1978. No other country in history underwent a more rapid and large-scale process of industrialization than China—an enormous transformation that within decades turned the country from an impoverished agricultural society into an industrial manufacturing powerhouse. Between the 1980s and today, China’s economy expanded at an average rate of approximately 10 percent.

Despite this massive growth, China is still classified as a developing country by most measures. For instance, its GDP per capita—USD$9,770 in 2018—is still comparatively low because of prevailing disparities in wealth distribution in the vast and unevenly developed country. While rising fast, average income levels in China are still comparable to those of Cuba or the Dominican Republic. That said, China in 2011 became the world’s second-largest economy and is on the brink of overtaking the U.S. as the largest economy, if it hasn’t overtaken it already. The country now has the world’s highest number of skyscrapers and the largest airport on the planet.

China’s middle class, likewise, has been growing at a breathtaking pace—a trend that helped fuel the recent leaps in higher education participation and outbound student mobility. By some estimates, the number of urban middle-class households in China—defined as those earning between USD$9,000 and USD$34,000 a year—will increase from just 4 percent in 2000 to 76 percent, or more than 550 million people, by 2022. Closely interrelated, “China’s urban population skyrocketed from 19 percent of the total population in 1980 to 58 percent in 2017.” What is remarkable about this transformation is that it has thus far not affected political stability. Unlike in other East Asian societies like South Korea or Taiwan, where economic modernization was followed by a push for democratization by newly emerging middle classes, China’s Communist Party (CCP) remains firmly in control.

DEMOGRAPHIC DECLINE AND OTHER PROBLEMS

That is not to say that China won’t encounter challenges on its path toward further development. Like other East Asian nations, China is now facing demographic decline and population aging. Despite the abolishment of China’s longstanding and rigid one-child policy in favor of its two-child policy in 2016, the country’s population is expected to begin contracting by 2027 due to factors like decreasing fertility rates, which recently dropped by 12 percent in 2018.

This demographic shift has already resulted in labor shortages with the workforce shrinking by 25 million workers between 2012 and 2017. On the flip side of this shortage of mid-level technicians, growing numbers of university-educated Chinese remain unemployed or underemployed amid an ever-expanding pool of university graduates. Many educated youngsters now find it increasingly hard to find good jobs, because their skills don’t match the needs of the Chinese labor market and, thus, are not in demand. Except for graduates in highly sought-after fields like engineering or information technology, rising numbers of university graduates end up working in the informal sector or in low-paying jobs, potentially a socially destabilizing development.

In response to these problems, the Chinese government is not only pouring massive resources into the modernization of Chinese universities and research institutes, it is also seeking to expand the country’s vocational training system. However, China’s export-driven economy is presently experiencing a significant slowdown amid the trade war with the U.S.—China’s largest trading partner—and a sluggish global economy, and other factors. While current economic growth rates still exceed 6 percent, any economic slowdown with negative implications for employment is of great concern to the CCP, whose political legitimacy largely rests on delivering increased economic prosperity.

Language of Instruction and Academic Calendar

The most common language of instruction in elementary and secondary schools is Mandarin, the main official language of China. In some regions where the majority of students are ethnic minorities, instruction is offered in both Mandarin and the dominant local language. Language policies vary by region. While China officially recognizes 55 ethnic minorities, the Uyghur language was recently banned as a language of instruction in parts of Xinjiang province. The CCP also seeks to curb the use of Tibetan as a language of instruction in Tibet.

In higher education, the language of instruction is predominantly Mandarin, although English-taught programs and courses are becoming increasingly common in an attempt to internationalize China’s higher education system. This is especially so at top-tier institutions that seek to attract more international students, the percentage of which is a criterion in international university rankings.

The academic calendar in both schools and universities runs from September to July. Universities usually divide the academic year into two semesters of 20 weeks each, although a few institutions use the quarter system. In semester systems, the last two weeks are usually reserved for examinations.

COMPULSORY EDUCATION: ELEMENTARY AND LOWER-SECONDARY EDUCATION

China’s Compulsory Education Law stipulates that all children must complete nine years of compulsory education, starting at the age of six or, at the latest, seven. Children can be enrolled in kindergarten at the age of two or three, but preschool education is not compulsory. The government is now pushing to universalize preschool education, however, and pouring sizable resources into the establishment of more kindergartens—the GER in preschool education recently jumped from 70 percent in 2014 to 82 percent in 2018.

Progress in elementary and lower-secondary education has been even more impressive. When China in 1986 adopted its compulsory education law, it set “two basic targets” (liang ji): universal basic education and literacy. The success of this drive can be judged by the fact that the enrollment rate for compulsory education was close to 95 percent in 2018, totaling 1.5 billion elementary and junior high school pupils nationwide. The illiteracy rate, meanwhile, has been reduced to 4.85 percent among those aged 15 or older, although this national average belies considerable regional variation between eastern metropolises and rural western regions. “Wealthy cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, reported 2014 literacy rates (98.52 percent and 96.85 percent) comparable with those of developed countries. At the other extreme, Tibet’s literacy rate was a mere 60.07 percent in [the] same year, pegging it closer to under-developed countries like Haiti and Zambia.”

Compulsory basic education generally comprises six years of elementary and three years of lower-secondary education and is free of charge at public schools. However, there is some variation between jurisdictions with a tiny number of them having a 5+4 rather than a 6+3 structure. Curricula and standards are set by the MOE in Beijing and then implemented nationwide by provincial and municipal governments.

Most schools are public, but the share of private schools is rising with 35 percent of elementary, junior secondary, and senior secondary schools being privately run as of 2018. In 2003, a law promoting the establishment of more private schools to expand capacity went into effect. According to the 2016 amended version of the law, these schools need to be licensed and comply with official regulations. Except for international schools that teach foreign curricula, Chinese schools follow the national curriculum. Private schools in the compulsory education sector are officially not allowed to operate as for-profit providers but may nevertheless charge tuition fees (which should be used primarily to pay for the school’s expenses); they may also receive subsidies and tax breaks from local governments.

The current curriculum follows the ministry’s Guidelines for Compulsory Education Curriculum Reforms, implemented nationwide in 2005. It encompasses moral education, Chinese language and literature, mathematics, art and music, and physical education. The third grade curriculum introduces science, a foreign language (generally English), and “comprehensive practice”, a subject that may entail community service, information technology education, or basic vocational education.

Pupils may remain within the same school or transfer to a local junior high school after the completion of elementary education. Either way, there is no selective entrance examination to access lower-secondary education in public schools (private schools may have different types of admission criteria). Entrance examinations existed until the 1990s but have been eliminated, so that children are now mandatorily enrolled in local schools based on residence.

The curriculum at this level expands on the basic subjects taught in elementary schools to include the additional subjects of history and geography, biology, physics, and chemistry. The foreign language taught at junior high schools is most commonly English, though schools may also offer Japanese or Russian, and students at some schools have the option of learning a second foreign language. There is no junior high school graduation examination. As long as pupils pass ninth grade, which generally means a score of 60/100 in core subjects, they are awarded the Compulsory Education Certificate (yiwujiaoyu zhengshu).

SENIOR SECONDARY EDUCATION

There are two types of schools at the senior secondary level: general academic high schools (gaozhong) and vocational high schools (zhongzhuan). The length of the regular program is three years, whereas three to four years may be required for vocational programs.

General High Schools

General high schools—of which there were 13,600 in 2017—enroll 60 percent of the total upper-secondary student population. They admitted over 8 million new students in addition to 23.7 million already enrolled in the same year.

To be admitted, students must pass an entrance examination (zhongkao) that is held during the final year of junior secondary school, in June or July of each year. While the MOE sets overall guidelines for the written exam, the exam is administered by local educational authorities and not standardized nationwide. It tests knowledge of the junior secondary curriculum and covers subjects, such as Chinese, mathematics, foreign language, political education, physics, and chemistry. Students must also pass a physical fitness test.

The zhongkao is an important benchmark in Chinese education. Educational authorities in the different jurisdictions use the test results to assign students to different schools with high grades being required for admission into top schools. Those with low scores can usually only be admitted into vocational schools. Overall progression rates from junior to senior secondary education, including both general and vocational tracks, have increased strongly in recent years, with 95 percent of lower-secondary graduates progressing to upper-secondary education as of 2017.

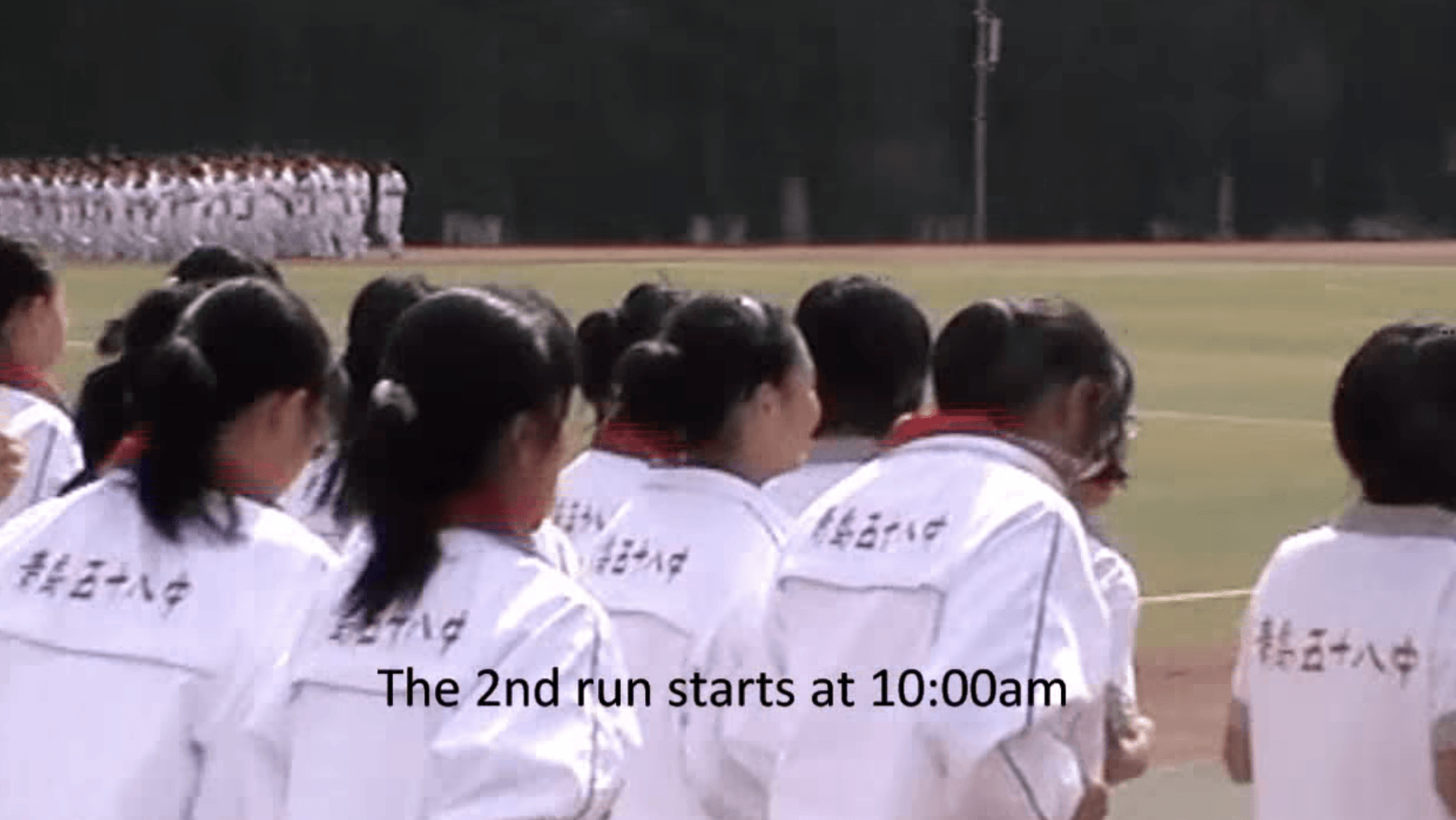

Once admitted, students traditionally had to choose between a science stream and an arts stream at the beginning of the 11th grade, after studying a general curriculum in 10th grade. However, the curriculum has recently been revamped to allow for greater customization—a change currently being phased in, in the different provinces. The reform introduces elective subjects and eliminates the practice of streaming since students can now elect subjects from both streams.

The old model was called 3+1, a formula that referred to the subjects later tested in the gaokao university entrance examinations. That is, three compulsory subjects (3)—Chinese, mathematics, and a foreign language, as well as one pre-set subject combination (1) of three subjects in the specialization stream: physics, chemistry, and biology in the case of science; and politics, history, and geography in the case of arts. In addition to these core subjects, there were other mandatory subjects, including arts, physical education, technology, and comprehensive practice. All these subjects were examined, but only the compulsory core subjects and the subjects from the specialization stream were tested in the gaokao. In this sense, the streaming concept largely predetermined which type of university programs graduates entered.

Under the current reforms, provinces will adopt one of two models referred to as “3+3” and “3+1+2.” The mandatory general subjects remain the same in both cases. But under the 3+3 model, students now can freely choose three electives from chemistry, biology, physics, geography, politics, and history. Students will typically choose their subjects based on the admission requirements for desired university programs. In addition, students can choose a number of electives from categories like vocational subjects, arts, or physical education.

The 3+1+2 model, on the other hand, is a partial reform that was adopted out of necessity. Since the new subject combinations will result in more classes and, thus, a need for additional teachers, students enrolled under this model will have fewer choices. They must choose between physics or history (1) and two electives from biology, chemistry, geography, and politics (2).

As shown in the graphic below, the new reforms have already been implemented in Shanghai and Zhejiang province. In other jurisdictions, the reforms will not be rolled out before 2022. Schools are hiring aggressively to accommodate the upcoming changes; retired teachers are also encouraged to come back to work to ensure a smooth transition.

To obtain a high school diploma, students must meet a minimum requirement of 144 credits and also pass a national graduation examination. This exam used to be called the General Examination for High School Students (huikao or joint exam) across most of China, but it has been phased out in recent years and will soon be completely replaced with the Academic Proficiency Test (APT, xueye shuiping ceshi) in all jurisdictions.

This graduation exam is based on the national curriculum set by the MOE but administered by local education departments. While the 3+x core subjects are examined at the end of grade 12, students can sit for examinations in the other subjects earlier and take the exam in parts, once they complete the necessary credit requirements in specific subjects. Graduates are issued a certificate of high school graduation.

VIDEO GALLERY

A few highlights from Keith's travels to China.

Share Page

STEALING FROM THE WORLD'S BEST SCHOOLS

What One U.S. Teacher Learned By Visiting Countries That Are Doing Education Right.